GASpangler

Member

TIME Europe

Steps Toward Heaven

July 5, 2004 | Vol. 164 No. 1

Lydia Itoi walked in the path of pilgrims who sought forgiveness along the 780-km trail called El Camino de Santiago. Unlike them, she knew where to eat

"Welcome, pilgrim," says the ragged knight in the dirty white cape, thrusting a burning tiki torch into my hand. "You've come just in time."

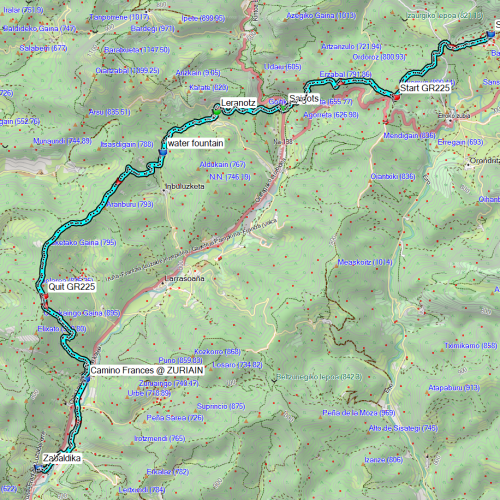

It is 11 a.m. on Day 26: 558 km into my 780-km walk across Spain on the great medieval pilgrimage route called El Camino de Santiago. The Way of St. James is not a single trail but a cobweb of paths threading through Europe to Santiago de Compostela on the northwestern coast of Spain, where the body of Santiago (St. James the Apostle) is said to have been miraculously discovered in the early 9th century. I've just trudged into Manjarín, a ruined pueblo slowly dissolving back into the misty mountainside, stone by stone. After three weeks of blisters, cramps and tendonitis, I feel about ready to dissolve myself.

That's when I encounter Tomás Martínez de Paz, Manjarín's most prominent (and only) permanent resident and a modern legend on the ancient trail. His thick white cape, emblazoned with the blood-red cross of the medieval Knights Templars, is tied over a camouflage vest. Under his arm he carries a broadsword wrapped in duct tape. When he tells me I'm just in time, I'm hoping he means time for coffee. But Tomás hustles me over to his pilgrim refugio, a derelict pile of granite with almost a whole roof. The yard is decorated like a paramilitary camp for Woodstock survivors. Flags fly over the rubble; across an old satellite dish someone has scrawled bring the soldiers home now! A stack of direction signs santiago, 222 km; rome, 2,475 km; machu picchu, 9,453 km lets me know precisely how far I am from nowhere.

Tomás pushes me in front of a harried young couple trying to hold a banner and a squirming little girl at the same time. Still wearing my pack and gripping the tiki torch, I stand at awkward attention while Gregorian chants and hymns of social protest crackle from a cassette player that wanted to give up the ghost long ago. As Tomás clangs a bell with his sword and prays for peace in Iraq, a riptide of delirium washes over me. My knees, calves and ankles seize up. I try not to collapse or set anything on fire.

Tomás, it turns out, once lived an ordinary middle-class subversive's life in Madrid. About 10 years ago, he left his family and proclaimed himself the last of the Knights Templars, the secretive order of medieval warrior monks who protected Christian pilgrims. The Templars disappeared after they were denounced and burned at the stake in 1307, but Tomás has lifted their standard over Manjarín. People can't decide whether to call him a saint or a madman. But if he is a modern-day warrior monk, I could use a little protection.

Let's face it, "pilgrim" is an eccentric title these days. Tomás may be a bit quixotic, but I've got the traditional talismans of a Santiago pilgrim: a scallop shell, a bottle gourd and a walking stick even if my stick happens to be a telescoping aluminum trekking pole. I've taken my place among the millions of pilgrims who have walked El Camino since the 9th century to pray at the saint's tomb. Over the last 400 years or so, the river of the faithful had slowed to a trickle, but now foot traffic is picking up again, as thousands of people some propelled by religious fervor, others by a taste for adventure attempt the Everest of Western pilgrimages. Making the journey today means following a dusty, stony footpath marked by graffiti yellow arrows when most of the world, including good stretches of the original pilgrims' way, has been paved over. It means checking contemporary secularism at the Romanesque church door and learning to go on faith.

But by anybody's standards, I am an unlikely pilgrim. As a food writer and professional hedonist, I spend most of my free time in temples of gastronomy, not tabernacles and certainly not gyms. My idea of adventure is telling the waiter to surprise me. So why am I here? I confess that I began my pilgrimage with an impure motive: to commit the sin of gluttony by eating my way across Spain, then walking it off. Camino purists preach culinary self-denial, but it's not for me. The trail runs through the most delicious landscapes in Spain: Basque country, garlanded with piquant red pimientos hung out to dry; the Rioja vineyards, where I imagined myself feasting on sun-sweetened grapes and spitting out the seeds as I walked; Castilla, with its tender milk-fed lamb and roast suckling pigs; and the final reward of Galicia, with its glorious shellfish feasts starring scallops, the symbol of Santiago himself. Other pilgrims carried lists of recommended refugios; I carried a list of must-eat restaurants.

Day 1, 0 km: St-Jean-Pied-de-Port Of the myriad routes that make up El Camino, I've taken the road most traveled, the Camino Francés. It leads out of the pretty French Basque hamlet of St-Jean-Pied-de-Port through the lopsided, crumbling medieval town gate called the Porte d'Espagne, then climbs almost a mile above sea level to cross the Pyrenees and the border into Spain. As if the ghosts of Charlemagne, Roland and Hemingway aren't enough, the road is lined with the graves of pilgrims who didn't make it.

Much of the landscape is wild, but it isn't wilderness. Although in the next month I will find myself trapped with running bulls, brush fires and a lecherous small-town mayor, my pilgrimage is not a medieval survival test. Most nights there will be a roof and bed, even if it is just floor space with 80 sweating snorers. There might be a shower curtain in the coed bathroom, or even, when I really need it, a good hotel. As much as I might like to play the adventurer, I'll do little epic battling against the elements unless you count walking into León on the shoulder of a highway in a blinding thunderstorm, dodging trucks and lightning. These days El Camino is more of a sanity test: the proverbial 40 days of wandering the spiritual wilderness, listening to your internal soundtrack. You discover that losing your mind isn't necessarily a bad thing. The first lesson a pilgrim learns is that most of the baggage we carry is useless.

Day 1, 23 km: Roncesvalles A 10-year-old British pilgrim boy with a pedometer figures out that it will take me about 1.1 million steps to get to Santiago. I spend a good percentage of those million steps wondering if I'm an authentic pilgrim. Although I'm walking the same road as the medieval pilgrims, I'm in awe of them. How can I try to walk even a mile in their sandals when I'm wearing j250 waterproof hiking boots? They set off for Santiago not knowing whether they would make it back alive, braving highway robbers, disease, miserable food and worse weather. No credit cards, no one-way flights home. They were assured of nothing but suffering and salvation.

Medieval indulgences worked something like modern frequent-flyer plans. For making the pilgrimage in a normal year, a pilgrim got a third of his sins struck off the books. For participating in a religious procession in Santiago, he got a 40-day free pass from purgatory, plus a 200-day bonus if the procession was led by a bishop. One hundred days free for going to Mass on the Monte de Gozo. And a plenary indulgence for going to Santiago in a Holy Year (like 2004, in which the July 25 Festival of St. James falls on a Sunday) or for any pilgrim who happened to die on the road. Not a bad deal, all things considered.

We latter-day pilgrims may have Internet-enabled gps cell phones, but the medieval pilgrims knew exactly where they were going and why. Modern pilgrims can't help envying their predecessors' clarity of moral purpose. On the other hand, I'm pretty sure that they would have envied our Gore-Tex. Dante defined the true pilgrim as one who tackled El Camino de Santiago, but his definition is too broad for some purists. So are the requirements of the Catholic Church's Pilgrim Office, which grants a certificate called the Compostela to anyone who has walked the last consecutive 100 km or biked the last 200. Camino puritans insist that a real pilgrim must walk with a pack, sleep in refugios and eat humbly. Bicycle pilgrims are beneath notice. Pilgrims on horseback are exotic, pilgrims with cars a travesty. It isn't going to Santiago that matters so much, it's how deeply you suffered to get there. After all, suffering is what separates a pilgrim from a tourist. If medieval pilgrims sought answers to prayers, modern pilgrims are just seeking answers. But after the first few hundred thousand steps, I have forgotten the question.

Day 3, 65 km: Pamplona I've learned to my horror that El Camino is actually designed to prevent pilgrims from eating well. I can't stop for a real meal during the day because my quivering legs might refuse to get moving again. At night, the better restaurants generally open at 9 p.m., but the refugios lock their doors at 10 p.m. I'd have to sleep outside or sneak in through a window like a delinquent teenager. And unwashed wine grapes, it turns out, can give you the runs.

But visions of food propel me. The knowledge that Chef Manoli Arza and her sisters were waiting in Pamplona to teach me the secret to preparing the pillowy white beans called pochas is the only thing that gets me over the Pyrenees. I had first tasted this Navarra specialty at their restaurant Hartza five years ago, and I have been craving them ever since.

My greed finds swift retribution on El Camino. I talk so much about my pocha paradise that other pilgrims start craving them too. After three days of slogging over the hills, I finally walk up to the door with my new friends Karla, a Brazilian engineering student, and René, a recently single Belgian-Canadian grandfather. Hartza is fancier than I remember, but maybe that's because I'm self-conscious about wearing muddy boots into a nice restaurant. Fortunately, the delicately simmered pochas are every bit as fluffy and ethereal under their feisty garnish of red and green peppers and chorizo as I dreamed on the hungriest kilometer. But my long-anticipated cooking lesson had disappeared. An even more voracious pilgrim named Olivier, a Frenchman living in England, had copied the address and gotten there first. The sisters assumed that he was the pilgrim food writer expected that day and taught him their special recipe. I resolve to talk less and walk faster.

Day 8, 184 km, NAjera Unless a pilgrim knows where to look, El Camino can be a purgatory of the menú peregrino, the pilgrim's fare usually consisting of limp salad, tough greasy steak or spaghetti, and the Spanish equivalent of a Twinkie. Some linguistically challenged pilgrims learn only the word bocadillo and condemn themselves to six weeks of sandwiches. Few things are more painful for me than watching people eating sandwiches in a world-class tapas bar. As a multilingual pilgrim, my biggest job is translating menus. Some pilgrims are curious to try new dishes, but many just want to avoid accidentally ordering things like blood pudding or pony carpaccio.

By now, the vegetarians are getting desperate. Spain has had a long history of giving short shrift to people who would rather not eat pork. Spanish food is relentlessly carnivorous. In desperation, most vegetarian pilgrims end up closing their eyes or compromising. Passing by a roadside snack bar on the way to Nájera, I meet a young, blond pilgrim who is busy devouring a shortbread cookie the size of a small platter. She says it's the best vegetarian food she has found in days. I don't have the heart to tell her it's a tarta de manteca (cake of lard). Day 11, 251 km: San Juan de Ortega By the time I cross the River Oca gorge and follow the yellow painted arrows over the steep, thickly wooded mountains, I have mastered the basic pilgrim's prayer. When the road is going up or the sun going down, it's a beseeching, "Please, please, please " When the road is gentle and the sun is rising, it's a fervent, "Thank-you, thank-you, thank-you." Once a rich and powerful spiritual complex, San Juan de Ortega now consists of a church, a monastery and the grimy Bar Restaurante Marcela, all standing in a row a one-stop pilgrim center. Calixtus, the curate's spotted white dog, is known to follow pilgrims for days until someone fetches him or sends him home in a taxi. He is nosing about the gravel lot, probably sniffing out his next guide to Santiago.

The church of San Juan de Ortega is sacred to civil engineers and barren women. Queen Isabel la Católica came here twice to take the fountain waters and pray for a miracle. Of her five children, two were named Juan and Juana, certainly a ringing endorsement for the local fertility treatment. As a childless woman hitting her mid-30s, I consider taking a sip from the miraculous fountain myself, but I chicken out having put off kids this long, it's become a habit. I wash my clothes in it instead.

Our spare underwear is flapping on the clotheslines in front of the church when the first visitors arrive to see the monastery's other miracle. By 5:30 p.m., the aisles are crammed with pilgrims and bus tourists, and the parish priest has to bang on the podium to remind the noisy crowd that we are in the house of God. The miracle of San Juan de Ortega is that a 12th century architect had the technical savvy to design a tiny window that catches a ray of sunset exactly on the spring and fall equinox. That feat, plus building some of the pilgrim roads and bridges we walk today, earned a civil-engineering sainthood for Juan de Ortega. But when the sun begins to set, scientific explanations fly out the window, and the miracle leaves us gaping in wonder like any pre-Copernican congregation.

A hush falls on the darkened church as a pinpoint of light appears in the lower apse wall. It travels slowly up in a smooth arc, drawing our eyes along the dusty, silent stone like a premodern laser pointer. The spotlight lands first on the Virgin, the central figure of an elaborately carved stone capital depicting the Annunciation, Visitation and Nativity scenes. The carving is tucked into an obscure corner, but the play of light draws back the curtain from the most poetic piece of Romanesque art we will see before reaching Santiago Cathedral itself.

The Virgin emerges calmly from the gloom, her robes flowing about her. Her expression is not that of a startled girl but a woman who accepts the implications of her position with faith and grace. She holds both hands up, palms outward, to receive the divine light, or else to shield her 900-year-old eyes from the tourists' flashbulbs.

Afterward, Father José María invites us pilgrims into the half-ruined monastery for garlic soup. Sopa de ajo, also called sopa castellana, is the poorest of dishes inspired by poverty: stale bread boiled in salted water. When there are more pilgrims, the sisters just add more water. This being Spain, they also add a touch of garlic and paprika. By some alchemy, the bread takes on the unctuous texture of something fatty and forbidden, and the broth, enriched with little more than charity, is hot and infinitely comforting. Restaurants tend to embroider their fashionably neo-rustic sopa castellana with chorizo, eggs and meat stock, but the simplicity of this parish soup proves the error of excess. Now this is perfect food for a pilgrim. Why is it that the priceless meals on my gastronomic Camino turn out to be the ones that are free?

Day 16, 339 km: Fromista I rest for a while in Frómista's heavily restored 11th century church of San Martín, widely considered to be the epitome of Romanesque Camino architecture, before treating myself to a nice dinner. The Church of San Martín is also famous for its collection of more than 100 carved capitals and 315 corbels, but most of the latter are replacements for the original racy collection showing a truly imaginative array of vices. Only one sinner escaped the censors and continues to seek his illicit pleasure under the highest church eaves.

My food flings are in direct violation of the code of pilgrimage as penance, but I can't seek enlightenment if I'm hungry. I give my fellow unrepentant sinner a last conspiratorial look, cross the street to the Restaurant San Martín, and order pimiento relleno con mariscos, a smoky red pepper valentine stuffed with shellfish and lovingly napped in a velvety seafood sauce. Next comes trucha escabechada, a whole fried trout marinated in vinegar sauce, followed by a soothing arroz con leche, cinnamon rice pudding. I sigh happily, stand up to compliment the manager, and pass out.

When I come to, I am lying on the deliciously cool tile floor and a group of French-speaking pilgrims is anxiously patting my wrists and waving stick deodorant under my nose. Louisette, a French-Canadian pilgrim in her late 70s who always walks too fast for me to keep up, lies nearby, swooning in sympathy. I decide to swear off overindulgence for a while.

Day 23, 463 km: Virgen del Camino I am already about two-thirds of the way to Santiago, but the spiritual logic of what I am doing here hasn't gotten much clearer. Surprisingly, only a few pilgrims, including my Brazilian friend Karla and a devout retired couple from Japan, look toward Santiago in the traditional Catholic sense of pilgrim faith. Most pilgrims I meet don't seem to believe or care if those are really holy bones lying in that far-off cathedral. At night we dream of reaching Santiago, yet Santiago himself is becoming less relevant to the pilgrimage named for him.

My buddy Emilio, a former teacher from Madrid and Camino history buff, is one of the strictest in following orthodox Camino pilgrim protocol, but he's a staunch atheist. He likes to sit next to me in Mass, contradicting the priest under his breath or quoting the Bible in Latin. Kathleen, a youthful-looking Californian with a radiant smile, explains to me over rice black with squid ink and fried baby eels that El Camino follows an earth-energy line under the Milky Way to Finisterre, and that the Catholics appropriated an ancient shamanistic pilgrimage dating to the Druids. Her vision of universal harmony on El Camino is as compelling and beautiful as she is.

Most of us are a muddle of motivations, finding or revealing new ones as we walk along. When I first met Karla, she said she was walking to celebrate her graduation, but she developed severe knee problems on the first day. She flatly refused to give in to her knees, trying to walk every day, riding the rest of the way. Even her mother begged her to come home. I can't understand why she wants to go through so much pain on what was supposed to be a vacation. She flicks her waist-length blond hair and says she is not a quitter. Besides, she is carrying a petition letter to Santiago on behalf of family members. We are cheering her every dogged step.

Some of us are in it for the fresh air. René has left his marriage and his trademark Canadian maple-leaf cap, but he has picked up another cap somewhere and is now masquerading as a Norwegian. Still, the Spanish sun is turning him into an unbelievable shade of red. Wolfgang, a former engineer from Germany with a wicked sense of humor, is taking full advantage of his retirement. He came to El Camino eager to conquer nature with all his latest hiking technology. But eventually, he gives himself up to romancing a soft-spoken German pilgrim named Andrea and being our commissar of fun. At times, he is too tipsy to find his own bed at night. René is the favorite target of Wolfgang's practical jokes, but they are inseparable. Luckily, El Camino has a tradition of relaxed pilgrim standards, as a centuries-old poem reassures: "The door is open to all, sick and healthy, not only to Catholics, but also to pagans, Jews, heretics and vagabonds." That covers just about all of us.

After finally extricating ourselves from the industrial skirts of León, Kathleen and I come to Virgen del Camino's startlingly contemporary church, decorated with tall, emaciated bronze statues and surrounded by frighteningly enthusiastic nut vendors. It is the feast day of the local patron saint, San Froilán, and Father Jaime Rodriguez Lebrato explains that these feast-day hazelnuts come with pardons. I am surprised, because I thought the Church had given up the sale of indulgences after Martin Luther, but I am always willing to try eating my way into a state of grace.

Day 29, 628 km: Triacastela I am no longer alone, and even in a world as idyllic as El Camino, that is a good thing. Besides the battle-tested comrades I've collected along the route, my courageous friend Susana has flown up from her busy life in Caracas, Venezuela, and joined me for the last segment of El Camino. We met up three days ago in the pretty little riverside village of Molinaseca, on the cusp of her family's native Galicia. Good hiking gear is scarce in Caracas, and Susana brings too heavy a burden. She was also foolish to try walking 30 km on her first day, and her knees have now swelled like Karla's.

Today we learn that pilgrims must also protect their idealism from those who see them as walking wallets. As we pass through yet another nameless stone pueblo with more cows than people, an old woman offers us some Galician plain-flour crepes called filloas. Kind people often bring food to the roadside to offer passing pilgrims, and we accept one each with a smile. We stop smiling when we hear the hefty price she asks only after we have taken a bite. Non-Spanish-speaking pilgrims leave without realizing they are expected to pay, and she curses them with impressive vehemence. A few hours later, a burly young man dressed as a pilgrim notices Susana limping as we stop to buy raspberries at a farmhouse. He introduces himself as Alfredo, whips out a medical kit and treats her knees with a pain-dulling spray. Emilio, Susana and I thank him profusely. When we finally totter into Triacastela, we bump into him as we are about to enter the refugio and he confides that the place is dirty and badly managed and that we would be better off in a charming private hostel he knows on the other side of town. Alfredo's recommendation turns out to be a dismal hovel, and we make the long walk back to the perfectly clean, sunny refugio. Of course, these shill games have as long a history as El Camino. The 12th century Santiago pilgrimage guide called Codex Calixtus warns of similar tactics practiced in this very same area, so we can't say we weren't warned.

Day 35, 761 km: Arca O Pino Hooray one day from Santiago and a refugio kitchen in good working order. We decide to throw a cake and champagne birthday party for René, who will turn 60 as we enter Santiago. For some reason, we had found many of the kitchens in Galicia out of commission, either broken, locked or lacking utensils. The hospitaleros apologize for the inconvenience, but some Spanish pilgrims mutter darkly about a conspiracy to channel business to local bars and restaurants.

The vegetarians are getting hungry again. Some are taking matters into their own hands and cooking over an open fire. Others take more radical measures. A few days ago, I bumped into Irini, a tall, lovely Greek Cypriot. When I first met her on the road from Logroño, on Day 8, she was a former vegan who by then had started eating eggs. But when I catch up with her again, she is walking alongside a golden, dreadlocked Adonis and she has a new recipe for my collection. "Guess what, I caught five fish! I cooked the most romantic meal ever." I stared at her. For a vegetarian, she'd become a crack fisherwoman. "Well, really I caught six. The sixth one, he was the most beautiful fish, but when I was trying to kill him like this" her hands twisted in a quick, bloodthirsty jerk "he jumped back in the water and got away." Why should I be surprised? On El Camino, there's always the chance for a late conversion.

Day 36, 780 km: Santiago de compostela On the last day of my journey, I suit up at 5 a.m. and tiptoe out of the Arca O Pino refuge dormitory to find my old walking companions Karla, Susana, René and Wolfgang standing with a large group in the entrance hall. It will be a short march to the cathedral, only about 19 km, but everyone wants to arrive in time for the noon pilgrims' mass. Normally, it is a race out of the front door. Today, we instinctively huddle together and wait for enough pilgrims to form a little army to move out and make our final assault on Santiago.

Outside, it is too dark to see. To lighten the mood, a jolly, scholarly Canadian pilgrim named Jacques takes out his harmonica and we sing an ancient song in pilgrim patois: "Ultreïa, ultreïa, e su seya, Deus, adjuva nos!"

Blindly, our lungs bursting, we stumble after the tinny strain of our pied piper. The sound of our own hoarse music links us together and to the invisible Camino. We can tell whenever there is a hill ahead because the harmonica goes quiet for a while, the minstrel too winded to play. We sing onward through the last scraps of eucalyptus forest, onward past the sleeping airport runways and drab suburbs, onward over the last rise and across the highway overpass, onward past the cross of San Pedro and the Plaza de Cervantes. We know that the cathedral, with its symphony in stone, the Portico de la Gloria carved by Master Mateo, waits just beyond the big arch up ahead, but we also know we could keep walking forever, to Finisterre and possibly to the ends of the earth. The shopkeepers smile and the tourists stare, but we sweep on past them singing, too far gone into the realm of pure spirit to care. "Onward, onward and forward, O God, help us "

Steps Toward Heaven

July 5, 2004 | Vol. 164 No. 1

Lydia Itoi walked in the path of pilgrims who sought forgiveness along the 780-km trail called El Camino de Santiago. Unlike them, she knew where to eat

"Welcome, pilgrim," says the ragged knight in the dirty white cape, thrusting a burning tiki torch into my hand. "You've come just in time."

It is 11 a.m. on Day 26: 558 km into my 780-km walk across Spain on the great medieval pilgrimage route called El Camino de Santiago. The Way of St. James is not a single trail but a cobweb of paths threading through Europe to Santiago de Compostela on the northwestern coast of Spain, where the body of Santiago (St. James the Apostle) is said to have been miraculously discovered in the early 9th century. I've just trudged into Manjarín, a ruined pueblo slowly dissolving back into the misty mountainside, stone by stone. After three weeks of blisters, cramps and tendonitis, I feel about ready to dissolve myself.

That's when I encounter Tomás Martínez de Paz, Manjarín's most prominent (and only) permanent resident and a modern legend on the ancient trail. His thick white cape, emblazoned with the blood-red cross of the medieval Knights Templars, is tied over a camouflage vest. Under his arm he carries a broadsword wrapped in duct tape. When he tells me I'm just in time, I'm hoping he means time for coffee. But Tomás hustles me over to his pilgrim refugio, a derelict pile of granite with almost a whole roof. The yard is decorated like a paramilitary camp for Woodstock survivors. Flags fly over the rubble; across an old satellite dish someone has scrawled bring the soldiers home now! A stack of direction signs santiago, 222 km; rome, 2,475 km; machu picchu, 9,453 km lets me know precisely how far I am from nowhere.

Tomás pushes me in front of a harried young couple trying to hold a banner and a squirming little girl at the same time. Still wearing my pack and gripping the tiki torch, I stand at awkward attention while Gregorian chants and hymns of social protest crackle from a cassette player that wanted to give up the ghost long ago. As Tomás clangs a bell with his sword and prays for peace in Iraq, a riptide of delirium washes over me. My knees, calves and ankles seize up. I try not to collapse or set anything on fire.

Tomás, it turns out, once lived an ordinary middle-class subversive's life in Madrid. About 10 years ago, he left his family and proclaimed himself the last of the Knights Templars, the secretive order of medieval warrior monks who protected Christian pilgrims. The Templars disappeared after they were denounced and burned at the stake in 1307, but Tomás has lifted their standard over Manjarín. People can't decide whether to call him a saint or a madman. But if he is a modern-day warrior monk, I could use a little protection.

Let's face it, "pilgrim" is an eccentric title these days. Tomás may be a bit quixotic, but I've got the traditional talismans of a Santiago pilgrim: a scallop shell, a bottle gourd and a walking stick even if my stick happens to be a telescoping aluminum trekking pole. I've taken my place among the millions of pilgrims who have walked El Camino since the 9th century to pray at the saint's tomb. Over the last 400 years or so, the river of the faithful had slowed to a trickle, but now foot traffic is picking up again, as thousands of people some propelled by religious fervor, others by a taste for adventure attempt the Everest of Western pilgrimages. Making the journey today means following a dusty, stony footpath marked by graffiti yellow arrows when most of the world, including good stretches of the original pilgrims' way, has been paved over. It means checking contemporary secularism at the Romanesque church door and learning to go on faith.

But by anybody's standards, I am an unlikely pilgrim. As a food writer and professional hedonist, I spend most of my free time in temples of gastronomy, not tabernacles and certainly not gyms. My idea of adventure is telling the waiter to surprise me. So why am I here? I confess that I began my pilgrimage with an impure motive: to commit the sin of gluttony by eating my way across Spain, then walking it off. Camino purists preach culinary self-denial, but it's not for me. The trail runs through the most delicious landscapes in Spain: Basque country, garlanded with piquant red pimientos hung out to dry; the Rioja vineyards, where I imagined myself feasting on sun-sweetened grapes and spitting out the seeds as I walked; Castilla, with its tender milk-fed lamb and roast suckling pigs; and the final reward of Galicia, with its glorious shellfish feasts starring scallops, the symbol of Santiago himself. Other pilgrims carried lists of recommended refugios; I carried a list of must-eat restaurants.

Day 1, 0 km: St-Jean-Pied-de-Port Of the myriad routes that make up El Camino, I've taken the road most traveled, the Camino Francés. It leads out of the pretty French Basque hamlet of St-Jean-Pied-de-Port through the lopsided, crumbling medieval town gate called the Porte d'Espagne, then climbs almost a mile above sea level to cross the Pyrenees and the border into Spain. As if the ghosts of Charlemagne, Roland and Hemingway aren't enough, the road is lined with the graves of pilgrims who didn't make it.

Much of the landscape is wild, but it isn't wilderness. Although in the next month I will find myself trapped with running bulls, brush fires and a lecherous small-town mayor, my pilgrimage is not a medieval survival test. Most nights there will be a roof and bed, even if it is just floor space with 80 sweating snorers. There might be a shower curtain in the coed bathroom, or even, when I really need it, a good hotel. As much as I might like to play the adventurer, I'll do little epic battling against the elements unless you count walking into León on the shoulder of a highway in a blinding thunderstorm, dodging trucks and lightning. These days El Camino is more of a sanity test: the proverbial 40 days of wandering the spiritual wilderness, listening to your internal soundtrack. You discover that losing your mind isn't necessarily a bad thing. The first lesson a pilgrim learns is that most of the baggage we carry is useless.

Day 1, 23 km: Roncesvalles A 10-year-old British pilgrim boy with a pedometer figures out that it will take me about 1.1 million steps to get to Santiago. I spend a good percentage of those million steps wondering if I'm an authentic pilgrim. Although I'm walking the same road as the medieval pilgrims, I'm in awe of them. How can I try to walk even a mile in their sandals when I'm wearing j250 waterproof hiking boots? They set off for Santiago not knowing whether they would make it back alive, braving highway robbers, disease, miserable food and worse weather. No credit cards, no one-way flights home. They were assured of nothing but suffering and salvation.

Medieval indulgences worked something like modern frequent-flyer plans. For making the pilgrimage in a normal year, a pilgrim got a third of his sins struck off the books. For participating in a religious procession in Santiago, he got a 40-day free pass from purgatory, plus a 200-day bonus if the procession was led by a bishop. One hundred days free for going to Mass on the Monte de Gozo. And a plenary indulgence for going to Santiago in a Holy Year (like 2004, in which the July 25 Festival of St. James falls on a Sunday) or for any pilgrim who happened to die on the road. Not a bad deal, all things considered.

We latter-day pilgrims may have Internet-enabled gps cell phones, but the medieval pilgrims knew exactly where they were going and why. Modern pilgrims can't help envying their predecessors' clarity of moral purpose. On the other hand, I'm pretty sure that they would have envied our Gore-Tex. Dante defined the true pilgrim as one who tackled El Camino de Santiago, but his definition is too broad for some purists. So are the requirements of the Catholic Church's Pilgrim Office, which grants a certificate called the Compostela to anyone who has walked the last consecutive 100 km or biked the last 200. Camino puritans insist that a real pilgrim must walk with a pack, sleep in refugios and eat humbly. Bicycle pilgrims are beneath notice. Pilgrims on horseback are exotic, pilgrims with cars a travesty. It isn't going to Santiago that matters so much, it's how deeply you suffered to get there. After all, suffering is what separates a pilgrim from a tourist. If medieval pilgrims sought answers to prayers, modern pilgrims are just seeking answers. But after the first few hundred thousand steps, I have forgotten the question.

Day 3, 65 km: Pamplona I've learned to my horror that El Camino is actually designed to prevent pilgrims from eating well. I can't stop for a real meal during the day because my quivering legs might refuse to get moving again. At night, the better restaurants generally open at 9 p.m., but the refugios lock their doors at 10 p.m. I'd have to sleep outside or sneak in through a window like a delinquent teenager. And unwashed wine grapes, it turns out, can give you the runs.

But visions of food propel me. The knowledge that Chef Manoli Arza and her sisters were waiting in Pamplona to teach me the secret to preparing the pillowy white beans called pochas is the only thing that gets me over the Pyrenees. I had first tasted this Navarra specialty at their restaurant Hartza five years ago, and I have been craving them ever since.

My greed finds swift retribution on El Camino. I talk so much about my pocha paradise that other pilgrims start craving them too. After three days of slogging over the hills, I finally walk up to the door with my new friends Karla, a Brazilian engineering student, and René, a recently single Belgian-Canadian grandfather. Hartza is fancier than I remember, but maybe that's because I'm self-conscious about wearing muddy boots into a nice restaurant. Fortunately, the delicately simmered pochas are every bit as fluffy and ethereal under their feisty garnish of red and green peppers and chorizo as I dreamed on the hungriest kilometer. But my long-anticipated cooking lesson had disappeared. An even more voracious pilgrim named Olivier, a Frenchman living in England, had copied the address and gotten there first. The sisters assumed that he was the pilgrim food writer expected that day and taught him their special recipe. I resolve to talk less and walk faster.

Day 8, 184 km, NAjera Unless a pilgrim knows where to look, El Camino can be a purgatory of the menú peregrino, the pilgrim's fare usually consisting of limp salad, tough greasy steak or spaghetti, and the Spanish equivalent of a Twinkie. Some linguistically challenged pilgrims learn only the word bocadillo and condemn themselves to six weeks of sandwiches. Few things are more painful for me than watching people eating sandwiches in a world-class tapas bar. As a multilingual pilgrim, my biggest job is translating menus. Some pilgrims are curious to try new dishes, but many just want to avoid accidentally ordering things like blood pudding or pony carpaccio.

By now, the vegetarians are getting desperate. Spain has had a long history of giving short shrift to people who would rather not eat pork. Spanish food is relentlessly carnivorous. In desperation, most vegetarian pilgrims end up closing their eyes or compromising. Passing by a roadside snack bar on the way to Nájera, I meet a young, blond pilgrim who is busy devouring a shortbread cookie the size of a small platter. She says it's the best vegetarian food she has found in days. I don't have the heart to tell her it's a tarta de manteca (cake of lard). Day 11, 251 km: San Juan de Ortega By the time I cross the River Oca gorge and follow the yellow painted arrows over the steep, thickly wooded mountains, I have mastered the basic pilgrim's prayer. When the road is going up or the sun going down, it's a beseeching, "Please, please, please " When the road is gentle and the sun is rising, it's a fervent, "Thank-you, thank-you, thank-you." Once a rich and powerful spiritual complex, San Juan de Ortega now consists of a church, a monastery and the grimy Bar Restaurante Marcela, all standing in a row a one-stop pilgrim center. Calixtus, the curate's spotted white dog, is known to follow pilgrims for days until someone fetches him or sends him home in a taxi. He is nosing about the gravel lot, probably sniffing out his next guide to Santiago.

The church of San Juan de Ortega is sacred to civil engineers and barren women. Queen Isabel la Católica came here twice to take the fountain waters and pray for a miracle. Of her five children, two were named Juan and Juana, certainly a ringing endorsement for the local fertility treatment. As a childless woman hitting her mid-30s, I consider taking a sip from the miraculous fountain myself, but I chicken out having put off kids this long, it's become a habit. I wash my clothes in it instead.

Our spare underwear is flapping on the clotheslines in front of the church when the first visitors arrive to see the monastery's other miracle. By 5:30 p.m., the aisles are crammed with pilgrims and bus tourists, and the parish priest has to bang on the podium to remind the noisy crowd that we are in the house of God. The miracle of San Juan de Ortega is that a 12th century architect had the technical savvy to design a tiny window that catches a ray of sunset exactly on the spring and fall equinox. That feat, plus building some of the pilgrim roads and bridges we walk today, earned a civil-engineering sainthood for Juan de Ortega. But when the sun begins to set, scientific explanations fly out the window, and the miracle leaves us gaping in wonder like any pre-Copernican congregation.

A hush falls on the darkened church as a pinpoint of light appears in the lower apse wall. It travels slowly up in a smooth arc, drawing our eyes along the dusty, silent stone like a premodern laser pointer. The spotlight lands first on the Virgin, the central figure of an elaborately carved stone capital depicting the Annunciation, Visitation and Nativity scenes. The carving is tucked into an obscure corner, but the play of light draws back the curtain from the most poetic piece of Romanesque art we will see before reaching Santiago Cathedral itself.

The Virgin emerges calmly from the gloom, her robes flowing about her. Her expression is not that of a startled girl but a woman who accepts the implications of her position with faith and grace. She holds both hands up, palms outward, to receive the divine light, or else to shield her 900-year-old eyes from the tourists' flashbulbs.

Afterward, Father José María invites us pilgrims into the half-ruined monastery for garlic soup. Sopa de ajo, also called sopa castellana, is the poorest of dishes inspired by poverty: stale bread boiled in salted water. When there are more pilgrims, the sisters just add more water. This being Spain, they also add a touch of garlic and paprika. By some alchemy, the bread takes on the unctuous texture of something fatty and forbidden, and the broth, enriched with little more than charity, is hot and infinitely comforting. Restaurants tend to embroider their fashionably neo-rustic sopa castellana with chorizo, eggs and meat stock, but the simplicity of this parish soup proves the error of excess. Now this is perfect food for a pilgrim. Why is it that the priceless meals on my gastronomic Camino turn out to be the ones that are free?

Day 16, 339 km: Fromista I rest for a while in Frómista's heavily restored 11th century church of San Martín, widely considered to be the epitome of Romanesque Camino architecture, before treating myself to a nice dinner. The Church of San Martín is also famous for its collection of more than 100 carved capitals and 315 corbels, but most of the latter are replacements for the original racy collection showing a truly imaginative array of vices. Only one sinner escaped the censors and continues to seek his illicit pleasure under the highest church eaves.

My food flings are in direct violation of the code of pilgrimage as penance, but I can't seek enlightenment if I'm hungry. I give my fellow unrepentant sinner a last conspiratorial look, cross the street to the Restaurant San Martín, and order pimiento relleno con mariscos, a smoky red pepper valentine stuffed with shellfish and lovingly napped in a velvety seafood sauce. Next comes trucha escabechada, a whole fried trout marinated in vinegar sauce, followed by a soothing arroz con leche, cinnamon rice pudding. I sigh happily, stand up to compliment the manager, and pass out.

When I come to, I am lying on the deliciously cool tile floor and a group of French-speaking pilgrims is anxiously patting my wrists and waving stick deodorant under my nose. Louisette, a French-Canadian pilgrim in her late 70s who always walks too fast for me to keep up, lies nearby, swooning in sympathy. I decide to swear off overindulgence for a while.

Day 23, 463 km: Virgen del Camino I am already about two-thirds of the way to Santiago, but the spiritual logic of what I am doing here hasn't gotten much clearer. Surprisingly, only a few pilgrims, including my Brazilian friend Karla and a devout retired couple from Japan, look toward Santiago in the traditional Catholic sense of pilgrim faith. Most pilgrims I meet don't seem to believe or care if those are really holy bones lying in that far-off cathedral. At night we dream of reaching Santiago, yet Santiago himself is becoming less relevant to the pilgrimage named for him.

My buddy Emilio, a former teacher from Madrid and Camino history buff, is one of the strictest in following orthodox Camino pilgrim protocol, but he's a staunch atheist. He likes to sit next to me in Mass, contradicting the priest under his breath or quoting the Bible in Latin. Kathleen, a youthful-looking Californian with a radiant smile, explains to me over rice black with squid ink and fried baby eels that El Camino follows an earth-energy line under the Milky Way to Finisterre, and that the Catholics appropriated an ancient shamanistic pilgrimage dating to the Druids. Her vision of universal harmony on El Camino is as compelling and beautiful as she is.

Most of us are a muddle of motivations, finding or revealing new ones as we walk along. When I first met Karla, she said she was walking to celebrate her graduation, but she developed severe knee problems on the first day. She flatly refused to give in to her knees, trying to walk every day, riding the rest of the way. Even her mother begged her to come home. I can't understand why she wants to go through so much pain on what was supposed to be a vacation. She flicks her waist-length blond hair and says she is not a quitter. Besides, she is carrying a petition letter to Santiago on behalf of family members. We are cheering her every dogged step.

Some of us are in it for the fresh air. René has left his marriage and his trademark Canadian maple-leaf cap, but he has picked up another cap somewhere and is now masquerading as a Norwegian. Still, the Spanish sun is turning him into an unbelievable shade of red. Wolfgang, a former engineer from Germany with a wicked sense of humor, is taking full advantage of his retirement. He came to El Camino eager to conquer nature with all his latest hiking technology. But eventually, he gives himself up to romancing a soft-spoken German pilgrim named Andrea and being our commissar of fun. At times, he is too tipsy to find his own bed at night. René is the favorite target of Wolfgang's practical jokes, but they are inseparable. Luckily, El Camino has a tradition of relaxed pilgrim standards, as a centuries-old poem reassures: "The door is open to all, sick and healthy, not only to Catholics, but also to pagans, Jews, heretics and vagabonds." That covers just about all of us.

After finally extricating ourselves from the industrial skirts of León, Kathleen and I come to Virgen del Camino's startlingly contemporary church, decorated with tall, emaciated bronze statues and surrounded by frighteningly enthusiastic nut vendors. It is the feast day of the local patron saint, San Froilán, and Father Jaime Rodriguez Lebrato explains that these feast-day hazelnuts come with pardons. I am surprised, because I thought the Church had given up the sale of indulgences after Martin Luther, but I am always willing to try eating my way into a state of grace.

Day 29, 628 km: Triacastela I am no longer alone, and even in a world as idyllic as El Camino, that is a good thing. Besides the battle-tested comrades I've collected along the route, my courageous friend Susana has flown up from her busy life in Caracas, Venezuela, and joined me for the last segment of El Camino. We met up three days ago in the pretty little riverside village of Molinaseca, on the cusp of her family's native Galicia. Good hiking gear is scarce in Caracas, and Susana brings too heavy a burden. She was also foolish to try walking 30 km on her first day, and her knees have now swelled like Karla's.

Today we learn that pilgrims must also protect their idealism from those who see them as walking wallets. As we pass through yet another nameless stone pueblo with more cows than people, an old woman offers us some Galician plain-flour crepes called filloas. Kind people often bring food to the roadside to offer passing pilgrims, and we accept one each with a smile. We stop smiling when we hear the hefty price she asks only after we have taken a bite. Non-Spanish-speaking pilgrims leave without realizing they are expected to pay, and she curses them with impressive vehemence. A few hours later, a burly young man dressed as a pilgrim notices Susana limping as we stop to buy raspberries at a farmhouse. He introduces himself as Alfredo, whips out a medical kit and treats her knees with a pain-dulling spray. Emilio, Susana and I thank him profusely. When we finally totter into Triacastela, we bump into him as we are about to enter the refugio and he confides that the place is dirty and badly managed and that we would be better off in a charming private hostel he knows on the other side of town. Alfredo's recommendation turns out to be a dismal hovel, and we make the long walk back to the perfectly clean, sunny refugio. Of course, these shill games have as long a history as El Camino. The 12th century Santiago pilgrimage guide called Codex Calixtus warns of similar tactics practiced in this very same area, so we can't say we weren't warned.

Day 35, 761 km: Arca O Pino Hooray one day from Santiago and a refugio kitchen in good working order. We decide to throw a cake and champagne birthday party for René, who will turn 60 as we enter Santiago. For some reason, we had found many of the kitchens in Galicia out of commission, either broken, locked or lacking utensils. The hospitaleros apologize for the inconvenience, but some Spanish pilgrims mutter darkly about a conspiracy to channel business to local bars and restaurants.

The vegetarians are getting hungry again. Some are taking matters into their own hands and cooking over an open fire. Others take more radical measures. A few days ago, I bumped into Irini, a tall, lovely Greek Cypriot. When I first met her on the road from Logroño, on Day 8, she was a former vegan who by then had started eating eggs. But when I catch up with her again, she is walking alongside a golden, dreadlocked Adonis and she has a new recipe for my collection. "Guess what, I caught five fish! I cooked the most romantic meal ever." I stared at her. For a vegetarian, she'd become a crack fisherwoman. "Well, really I caught six. The sixth one, he was the most beautiful fish, but when I was trying to kill him like this" her hands twisted in a quick, bloodthirsty jerk "he jumped back in the water and got away." Why should I be surprised? On El Camino, there's always the chance for a late conversion.

Day 36, 780 km: Santiago de compostela On the last day of my journey, I suit up at 5 a.m. and tiptoe out of the Arca O Pino refuge dormitory to find my old walking companions Karla, Susana, René and Wolfgang standing with a large group in the entrance hall. It will be a short march to the cathedral, only about 19 km, but everyone wants to arrive in time for the noon pilgrims' mass. Normally, it is a race out of the front door. Today, we instinctively huddle together and wait for enough pilgrims to form a little army to move out and make our final assault on Santiago.

Outside, it is too dark to see. To lighten the mood, a jolly, scholarly Canadian pilgrim named Jacques takes out his harmonica and we sing an ancient song in pilgrim patois: "Ultreïa, ultreïa, e su seya, Deus, adjuva nos!"

Blindly, our lungs bursting, we stumble after the tinny strain of our pied piper. The sound of our own hoarse music links us together and to the invisible Camino. We can tell whenever there is a hill ahead because the harmonica goes quiet for a while, the minstrel too winded to play. We sing onward through the last scraps of eucalyptus forest, onward past the sleeping airport runways and drab suburbs, onward over the last rise and across the highway overpass, onward past the cross of San Pedro and the Plaza de Cervantes. We know that the cathedral, with its symphony in stone, the Portico de la Gloria carved by Master Mateo, waits just beyond the big arch up ahead, but we also know we could keep walking forever, to Finisterre and possibly to the ends of the earth. The shopkeepers smile and the tourists stare, but we sweep on past them singing, too far gone into the realm of pure spirit to care. "Onward, onward and forward, O God, help us "