Some Notes & Advice on the Pilgrimage Circuit to the 88 Temples of Shikoku, Primarily Conceived for Curious Non-Japanophone Parties Who Have Walked the

Camino de Santiago

In the summer of 2009, in part for reasons of friendship and malaise and in part for reasons that, even now, remain obscure to me, I left my apartment in Berlin and met my friend Tom in St. Jean-Pied-de-Port; we set off in the early morning of June tenth and arrived in Santiago de Compostela some thirty-three days later, where we indulged erstwhile vices for two days before walking the final hundred kilometers to Finisterre. My account of that trip was published at indefensible length in the literary quarterly McSweeney’s, and I’ve made a pdf copy available here.

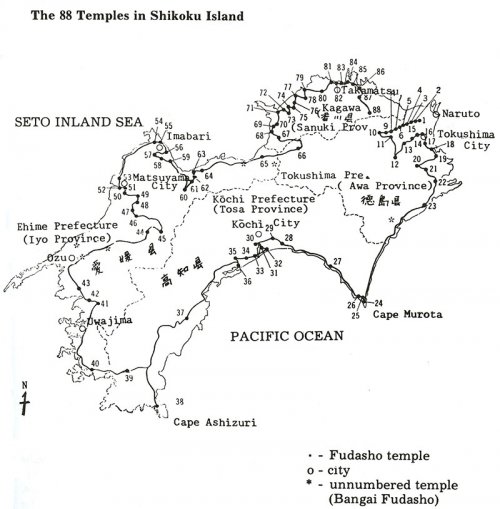

While on the Camino, I met three Japanese pilgrims, one a charming and thoughtful phd candidate in anthropology at the University of Tokyo, the other an older couple who had driven the Camino on their honeymoon and were back to see what it would be like to walk it; each of them told me about the Shikoku o-henro and suggested I might find it of some interest. I read a bit about Shikoku and readily agreed, and when Tom and I arrived at the ocean I knew I had only begun to work through the questions that, in one form or another, drew me to the Camino in the first place: what it means to travel with some vague expectation of transformation; why a Medieval religious pilgrimage had gained, over the last twenty years, such a strong secular following; what the differences are between experiencing a distant place as a pilgrim vs. as a tourist (‘tourist’ being the antagonist whose contrast helps the pilgrim understand what differentiates her journey, with its structure, its mythology, and its privation, from mere sightseeing); how pilgrimage offered history’s first pretext for an experience of elsewhere; and how pilgrimage travel provides for a satisfying ratio of obedience and belonging (you are in thrall to the authority of an old set of rules, and keep pace with others in similar thrall) to license and digression (those rules allow idiosyncrasy and surprise and nonfungible personal experience). I decided that all of this might make for a small and digressive book on pilgrimage, a kind of anti-travelogue about restlessness, borrowed authority, and communities of austere purpose; I drew up a proposal and was lucky enough to sell it, to Riverhead, a few months later. In the late winter of 2010 I took the boat from Shanghai to Kobe, and on the first of March I — along with my grandfather, who would be joining me for the first ten temples — bought a hat and a staff at Temple 1, Ryôzenji, and began to circumambulate Shikoku. I returned to Ryôzenji, this time from the opposite direction, thirty-nine days later.

I can say with some reasonable anecdotal confidence that most of the foreigners who walk the Shikoku o-henro have first walked the Camino. The Camino is an unusually vivid experience, and it’s not difficult to understand why someone might cast about, especially in the immediate post-partum lull, for something similar. Thanks to Dave Turkington and David Moreton, there is a wealth of good resources for gaijin pilgrims to be found online, but as I walked, in inevitable and constant Camino-comparative reverie, it struck me that there ought to be some information available specifically for those who have completed the Camino and are considering taking up the o-henro. The below is not intended to be a comprehensive guide; for information about the history of the circuit, where to start, what to bring, etc, I encourage you to visit Turkington’s site. (The one thing I will add to his site is that it’s absolutely possible to do it with virtually no Japanese, though I recommend you learn at least the numbers and basic greetings before you go; it’s also pretty useful to learn the kana, but that’s slightly more of an investment. There are also excellent iPhone Japanese/English dictionaries that made my interactions considerably easier.) The following is, rather, an ad hoc catalogue of advice I might have wanted to hear between finishing the Camino and setting out for Shikoku. I’m afraid much of this will seem discouraging, but that’s not my aim. The Shikoku o-henro is not particularly fun, or at least not fun in the way the Camino frequently was, but it does have distinct rewards of its own. (That said, the one American I walked with for a few days in Shikoku said that he found the Camino much more difficult, emotionally and physically, but he had done it in February and admitted he was carrying something like sixty pounds of luggage for some reason.) If you go into the o-henro expecting an experience that much resembles the Camino, however, you will no doubt find yourself disappointed and frustrated, and I offer the below advice with the idea that the sooner you abandon the hope that it will feel like a

Camino de Santiago with sashimi rather than bocadillos, the better off you will likely be.

I’m more than happy to correspond about either the Camino or the Shikoku o-henro, especially with those who have done one and are considering the other, and can be reached at gideonlk [at] gmail [dot] com.

***

1. The Shikoku o-henro is vastly more difficult than the

Camino de Santiago.

It’s not just that the o-henro is, depending on whether you visit the bangai or not, four to six hundred kilometers longer, though there was a brief moment of despair when I got to Matsuyama and realized I’d just completed the equivalent of the Camino and still had two weeks to walk. Ninety percent of the Camino is on paths of one variety or another; ninety percent of the o-henro is on asphalt roads. Imagine the last fifteen or so kilometers arriving at Burgos, when you come down out of the mountains on that exceedingly pleasant forested trail, abruptly hit a road, walk the access lane around the airport, and then consider killing yourself as you trudge along a four-lane exhaust-cloud artery lined with blocky warehouses and ferreterías. That interim right there is, with little exaggeration, most of the o-henro, though the o-henro has the additional pleasure of long, airless tunnels, as well. The trail is rarely quiet and almost never soft, and at times the proximity and speed of the traffic makes it feel unsafe. Much of the trip looks like this, but with a parade of trucks:

empty road

When it is quiet and soft, it’s because you’re going up and down mountains. These are almost without exception the most pleasant and memorable stretches of the o-henro, but they are also far more strenuous than almost any given section of the Camino. There are at least two days that are as long and arduous as the Camino between St. Jean and Roncesvalles, the climbs to T12 and to T60, and there are more than a dozen stretches that are steeper than the ascent to O Cebreiro (the approaches to T20, T21, T27, and, though it’s short, T35; the two passes between T36 and T37; the pass between T39 and T40, entering Ehime Prefecture, and then the one between T40 and Uwajima City; the two passes between T43 and Ôzu City; the long, unbroken ascent from Ôzu City to T44, and then the constant up and down to T45 and back; the peak at T60; the trail and steps to T71; the plateaux at T81 and T82 and then at T84; and, finally, the advance upon T88, if you take the path rather than the road.) These sections are, as I’ve said, far more appealing:

Hiking boots are almost certainly overkill and will hurt your feet on the asphalt more than they’ll help you in the mountains; I recommend the most comfortable and thickly padded running sneakers you can find. They’ll get soaked when it rains but there’s little you can do about that, and you ought to have an opportunity to dry them at night.

2. The Shikoku o-henro has not, at least to my knowledge, been parsed into stages the way the Camino has, nor does it lend itself to an easily adopted itinerary.

This is perhaps even more difficult to grow accustomed to than the asphalt. The Camino requires almost nothing in the way of logistical effort or skill; even if you chose not to walk with a guidebook, the xeroxed sheets they give out in St. Jean, and which are available along the way, break it up into thirty or thirty-one stages of average difficulty. Even if you don’t follow the normal, prescribed stages, you very rarely find yourself having to walk more than eight or ten kilometers, at the absolute most, without finding an albergue, and you never have to make a reservation in advance. As far as the actual trail goes, there are yellow arrows approximately every four feet, so even the world’s least oriented bozo can make his or her way without too much trouble.

None of this is true for the o-henro. It is possible that, for Japanese speakers (as I said, I can’t count myself among them), there are websites and books that say things like, ‘If you want to finish in about forty-five days, we suggest you walk to T8 on the first day, T11 on the second, T12 on the third, T17 on the fourth,’ and so on, but as far as I can tell nothing of the sort exists in English. Even if it did, however — and I’ve given some thought to offering a proposed forty-five-day itinerary here, and may yet do so — it wouldn’t be nearly as useful, because you’ve got a much narrower margin to tailor it to your own pace. There are plenty of places along the henro trail without an overnight accommodation for twenty kilometers, which means that you’ve got to put considerably more thought into how you break up the route. (This is especially true if you’re sleeping in henro huts, which can be few and far between, though it’s not quite as true if you’ve got a tent; more on accommodation in a moment.) Furthermore, the henro trail, while apparently much better than it once was, isn’t marked nearly as well as the Camino is, which means you’ve got a far better chance of getting lost, and the stakes are much higher when you do. Incidentally, the same thing goes for food; you almost always have to at least pay attention to the prospects for the next two meals, since it’s not unusual to go eight hours without much in the way of a market.

Insofar as there’s a solution to this, my advice is, if you can afford it, to stay in the ryokan and minshuku, especially the recommended ones (David Moreton has starred some in his guidebook, and they seemed like universally good recommendations). The inn proprietors will know the local henro trail and, even if you don’t speak Japanese, they’ll be able to help you make an informed and reasonable decision about the next day’s leg, and then will be more than happy to make a reservation for you for the next evening. I stayed at some places where the proprietor even had a local map with distances indicated; there were two ryokan marked at twenty kilometers, another at twenty-four, another at thirty, and so on, so I could just tell him I’d been averaging about thirty-five clicks a day and he had an immediate recommendation. One time I told a ryokan proprietor that I was planning on making a certain temple the next day and he insisted it was too far for one day and made a reservation for me five or six kilometers closer; he was right. The other thing that only the locals will know is the condition of the trail. Especially if you’re walking in the early spring, as I was, there will be places where the trail is in bad shape, and a local will, for example, tell you to take a parallel road instead of the usual one. There is no other way to know this sort of thing; you can try to ask at the temples themselves, but especially when there are big bus tours you most likely will not get the same quality of attention. Overnighting at places that are going to be able to give you advice like this is invaluable, and once I figured that out I wished I’d been doing it from the beginning. They are also just obscenely comfortable:

That said, it’s far more expensive; as the various websites mention, a night in a ryokan or minshuku without food will cost anywhere from 3500—4500¥, and with food (two meals) will be 6000—9000¥. Without food this is still cheaper than a hotel (business hotels tend to run around 4500—6000¥/nt), but it’s certainly not budget travel. Having spent the first half of my o-henro sleeping outside — in huts and bus stations and once in a mountain shrine — and most of the second half in ryokan and minshuku, I can say with no hesitation that the latter is a much easier, more pleasant, and less anxious way to make the circuit. It’s also, even if most people won’t speak much English, less lonely. (See next note.) If you are going to sleep outside, do bring a tent, and if you’re going to start before April you ought to make sure your sleeping bag is rated to below freezing.

3. The Shikoku o-henro is profoundly solitary.

One of the wonderful things about the Camino is that you’ve almost always got the option of company; if you want to walk alone, you can, but if you hit the old slough of despond there’s usually someone to walk alongside for an hour or a week. This is not true in Shikoku. On an average day on the island, I probably saw two or three other walking pilgrims, though there were days I saw a dozen and days I saw nobody at all. I met four foreigners: a fifty-year old American sleeping mostly in huts, a young Australian couple with a tent, and a nineteen-year-old American whose notes in guestbooks I saw along the way and whom I finally encountered at T88. There was also apparently a Quebécoise some days ahead and a Swiss woman about a week behind. That was it, and I’m given to understand that even that was a lot. I met four Japanese walkers who spoke some English and wanted company, but that was only toward the end, when I was staying more consistently in ryokan and had a chance to meet other henro on foot. For me a significant aspect of my Camino experience was the rich and spontaneous community that Tom and I found ourselves a part of along the way, and the loneliness of the o-henro was something that, even if I was aware in the abstract that I’d be mostly left to my own devices, I was not entirely prepared for.

4. You absolutely need a map.

This is more of a corollary to #2 above. Most of the people we met on the Camino didn’t have a guidebook; they either had the xeroxed stage recommendations or nothing at all. The signage and relative frequency of villages and albergues make this possible. But there is simply no way to do the o-henro without a guidebook. The only English map book is the one David Moreton put together, which is available on his website. In the attempt to make a book small enough to fit in a pocket, though, the maps in the Moreton book aren’t always drawn to the most useful scale, so my strong recommendation is that you also purchase the standard yellow Japanese map book; it’s available everywhere once you arrive and isn’t very heavy. Though it takes a little getting used to — the maps are cut up in counterintuitive ways, and there’s no consistency to where north is, so you’re always spinning the book like some paper DJ — but they’re extremely helpful once you’ve gotten used to them, and they contain much more information (including a great deal of topographical detail) than Moreton had room for. They also show all the alternative routes with the varying mileages marked off; for the most part Moreton only indicates major alternatives, and often it’s hard to tell from his maps what the differences are and which is the standard route. Use the two together. It’s worth the extra weight.

5. It will definitely rain and will probably rain a lot.

I know that most people hit inclement weather over the Pyrenees or throughout Galicia, but Tom and I were lucky enough to have only about ten minutes of rain the entire Camino. In Shikoku it rained for about half the time I was on the circuit, and often it poured. One day it hailed. And if you start, as I did, on the first of March, it will be cold enough in the mornings for gloves; when I walked toward T44, up and out of Ôzu City, there was frost on the windshields, and by then it was almost April. I think, in retrospect, that I started a bit too early — weatherwise I’d suggest starting closer to April 1, if you can — but I was worried that it would be hard to travel during Japan’s Golden Week, the first week in May, so I wanted to finish by then.

6. There is no internet.

This seems like a trivial thing, I know, but many people start the Camino thinking they’ll be in only very intermittent touch and then are pleased to discover that so many of the albergues and cafés have internet available. The other foreigners I met in Shikoku were all planning, they told me, to blog, but were surprised to find pretty much no internet at all outside of the four provincial capitals. All Japanese people have internet on their phones, so there’s no need for an internet-café infrastructure. That said, if you’re resourceful you can find it — at, for example, the Michi-no-Eki stops, or at the town and prefectural offices — but if you’re looking to blog or be in regular touch you ought to bring along an iPhone or iPod Touch that you can use over wireless networks. (Even the smallest villages usually, with a little searching, had an open wireless network somewhere.) I advise against a laptop for reasons of weight and of rain.

I may update this page as new suggestions occur to me, but for the moment that covers what I think anybody considering the circuit ought to know. If you’ve done both pilgrimages and have further suggestions, by all means please do be in touch.

— Gideon Lewis-Kraus